We had the pleasure of welcoming Robin Amado into our class this past week as a guest instructor while Omar was away in Alaska. Robin brought us delicious banana bread (it was still warm!) and led the class through a thoughtful discussion on partnerships and cultural competence. This was particularly relevant, as we are starting to really dig-in to our TLAM projects, working closely either with the Red Cliff or Oneida Nations. We’ve visited these communities and hope to build positively on the rich partnerships that have already been developed by those TLAMers who came before us. But we still have a lot to learn about and from our communities.

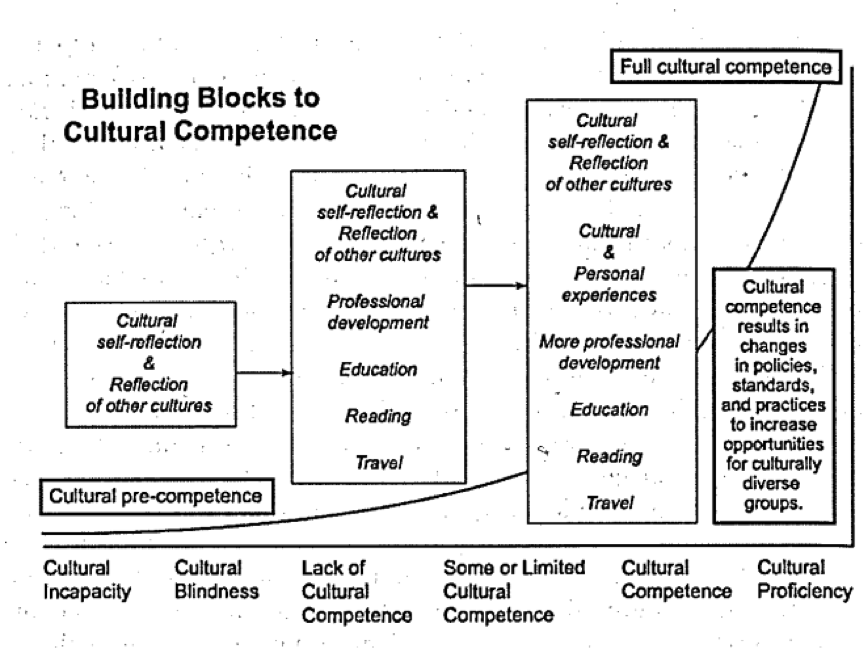

So what is cultural competency and how will it help us, both now and in our futures as library professionals? We read from several articles that touched on building understanding and partnerships for both information professionals and university researchers working with American Indian and other minority communities. The following are some common themes we identified in our readings and discussion.

You must know about yourself and your own culture to better understand others. Having personal awareness is key to being sensitive of other cultures and developing honest relationships. Reflecting on your own culture and customs will open your heart to understanding others.

Listen carefully and pay attention. We reflected on our visits up to Oneida and Red Cliff and all agreed that careful listening was something we made an effort to do. To better understand our project partners and their communities, we had to be quiet and listen first. Along with listening, it’s also important to leave any pre-conceived notions of the community at the door and listen with an open mind.

Slow down—building meaningful relationships takes time. Rushing to meet a deadline should never take precedence over cultivating an honest working relationship—and this can take time.

Respect Indigenous ways of Knowledge. It can be easy to forget that not everyone shares the dominant view of knowing, understanding, and communicating. One of my favorite examples of cultural sensitivity from our readings this week comes from a group of researchers who adapted their methods of collecting data from focus groups to sharing circles, in which they were also active participants. They were expected to “speak spontaneously”—which means waiting until it is your turn to speak before deciding what to say. In the culture they were working with it is thought that if you are thinking of what to say next, you aren’t actively listening to the person who is speaking. This goes against a lot of what most of us are taught—to think before you speak. Yet it makes sense—it’s more important to be listening.

Be aware of historical transgressions and their impact on building trust. This is important for everyone working in tribal communities, but may be especially relevant for researchers. Be aware of past work done with the community by outsiders—it’s important to be patient and sensitive to the scars left by others.

Finally—Learn about the culture you’re working with. As we learned during our first week of TLAM, there are 12 tribes in Wisconsin, and all of them are unique—even the different bands of Ojibwe have diverse histories and customs. It’s important to learn as much as you can about the specific history and culture of the tribe you are working with, and remember that you can only get so much from books! Published histories may be written by an outsider and may not contain accurate or culturally sensitive information. This means spending time with the tribe you’re working to build a relationship with and learn directly from community members.

These are just some of the concepts that we discussed in class—and having this conversation is just one step in becoming culturally competent as we work with Red Cliff or Oneida. Before class ended, Robin reminded us that our work with these tribes this semester is a mutually beneficial relationship, and to keep in mind that we are doing this work to benefit the communities and to gain skills for ourselves. Thanks for a great class, Robin! And the banana bread, too!

-Molly McBride